Exploring Why So Many Rap Artists Die Young — Hip-Hop And Health

Hip-hop and health – why so many rap artists die young.

The song “Be Healthy” from the 2000 album by hip-hop duo dead prez, “Let’s Get Free,” is a rare rap anthem dedicated to diet, exercise and temperance:

“They say you are what you eat, so I strive to eat healthy / My goal in life is not to be rich or wealthy / ‘Cause true wealth come from good health and wise ways / We got to start taking better care of ourselves”

In what’s widely recognized as hip-hop’s 50th anniversary, an unfortunate reality is that several of its pioneering artists aren’t here to celebrate. The number of rappers who never live to see much more than 50 years themselves is astounding.

Rappers and rap fans can’t help but take notice that their peers and favorite rappers are dying young. Trugoy the Dove of De La Soul, 53, passed away in February 2023 after a battle with congestive heart failure. Gangsta Boo, hailed as the “Queen of Memphis” and known for her work with Three 6 Mafia, died at the age of 43 of a drug overdose in January 2023. Takeoff, a member of the Atlanta trio Migos, was killed in November 2022. He was 28 years old.

Rapper Jim Jones has claimed that rap is the most dangerous profession due to rappers being violently killed so frequently. Similarly, rapper Fat Joe believes rappers are an endangered species. In the 2022 song “On Faux Nem,” Lupe Fiasco put it more succinctly: “Rappers die too much.”

As a rapper, a fan of hip-hop’s art and artists, and a professor of hip-hop, I agree with Lupe Fiasco: Rappers die too much. Whether it’s from gun violence, heart disease, cancer, self-harm or drugs, the number of rappers whose lives have ended prematurely is alarming.

The (un)exceptional spectacle of American gun violence

Stories of rappers who die violently are well known. News media are quick to report on violence in hip-hop to support their view that the music and the people who make it are exceptionally violent. Violence, death and conflict attract attention. Pair any of those with racial stereotyping and scapegoating and it’s easy to see why the murders of hip-hop stars such as Nipsey Hussle, the Notorious B.I.G., Tupac Shakur and countless other artists garner so much attention.

Though they were all taken by the very American plague of gun violence, news and historical accounts often amplify the spectacle of violent Black death, even when they claim to honor those who are killed.

I’ve written extensively about the trend of scapegoating rappers. It is also the topic addressed in the song “ANKH” from my forthcoming mixtap/e/ssay, “V: ILLICIT”:

“He died by the gun but they blamed the music. / They said, ‘What he said was evidence.’ And used it. …/ No compassion for the life torn apart when the bullets hit him, / cause he talked about the block in his art, so he’s not a victim. / Cameraman said, ‘They don’t value life too much.’ / He reported here before. Even twice some months. / Somewhere in his mid-twenties was his deadline (dying). / ‘Another N— Killed Here’ was the headline (crying).”

An awful byproduct of this culture of consuming carnage is that the kinds of violent gun tragedies people are experiencing all across the U.S. are being spotlighted in hip-hop and used as excuses to criminalize and pathologize certain people and the music they enjoy, the art they create, the neighborhoods they live in or the places they grew up.

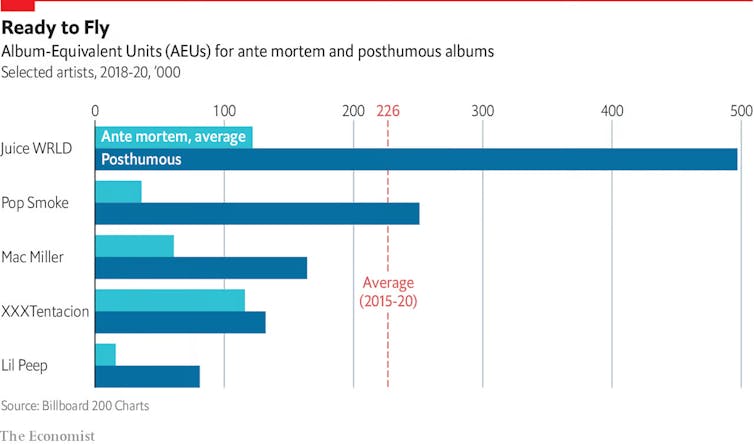

Another heartbreaking consequence is that some rappers only gain wide popularity and realize financial success after they’ve died. Deceased rappers are an unfortunately abundant commodity. Juice WRLD and Pop Smoke are prime examples: They both sold four to five times as much music after their deaths than when they were alive.

The Economist

Along with being alarmed by these tragedies, it’s important to examine the conditions that affect mortality and attempt to get to the actual causes rather than scapegoating a musical form.

Deadly diseases

While violence brings about headlines, guns are not the only cause for concern. Diseases – many of them preventable – are also a factor.

Heart disease, lung disease, cancer, diabetes, strokes and renal disease are among the top 10 causes of death among Black men and Hispanic men, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It makes sense that these causes also prominently figure in the deaths of hip-hop artists.

Gone before retirement

Rapper and producer J-Dilla (32), rappers Big Moe (33), Black the Ripper (32) from the U.K., Lord Infamous (40), KMG the Illustrator (43 from Above the Law, DMX (50), Big T (52), Tweedy Bird Loc (52), Black Rob (52) and Big Pun (28) all died from heart attacks. Heavy D (44) experienced a pulmonary embolism that led to his death. Prince Markie Dee (52) of the Fat Boys passed away from congestive heart failure. Craig Mack (47) died from heart failure. And Brax (21) died from cardiac arrhythmia.

Phife Dawg (45) of A Tribe Called Quest, Tim Dog (46) and Biz Markie (57) all passed away from complications related to diabetes.

Guru (48) of Gangstarr, Bushwick Bill (52) of the Geto Boys, Hurricane G (52) and Kangol Kid (55) died from cancer. DJ K Slay passed away at 55 from what was described as COVID-19 complications.

Eazy-E died of AIDS at 30.

Nate Dogg’s death at 41 was attributed to a stroke.

Pimp C’s death at 33 was attributed to sleep apnea and an overdose of cough syrup. Lexii Alijai (21), Chynna (25), and Shock G (57) all reportedly died of accidental drug overdose.

Ms. Melodie passed away in her sleep at the age of 43. Big Pokey collapsed onstage and passed away at 48. Ecstasy of Whodini died at 56.

A renewed focus on health

Unfortunately, this list of tragic lives halted from ages 21 to 57 is not a comprehensive account of all the rappers who have passed away well before the age of retirement.

The occasion of celebrating 50 years of hip-hop provides a moment to reflect and honor some of the artists who contributed to the culture and are not here to celebrate this golden anniversary. It’s also, perhaps, an opportunity to consider some of the outcomes of systemic barriers to health and wellness, such as access to affordable health care, varied dietary options and mental wellness resources.

Given the number of rappers and other prominent hip-hop artists who have died young, ultimately it may come down to seriously taking heed to dead prez’s instructions from “Be Healthy”: “We got to start taking better care of ourselves.”![]()

A.D. Carson, University of Virginia

A.D. Carson, Associate Professor of Hip-Hop, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.